Constipation

Overview

Other Names & Coding

K59.00, Unspecified

K59.01, Slow transit constipation

K59.03, Drug-induced constipation

K59.04, Chronic idiopathic constipation

K59.09, Other constipation

R15.1, Fecal smearing or soiling (encopresis)

F98.1, Encopresis not due to a substance or known physiological condition

ICD-10 for Constipation (icd10data.com) provides further coding details.

Prevalence

Genetics

Prognosis

Practice Guidelines

Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, Faure C, Langendam MW, Nurko S, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y, Benninga MA.

Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and

NASPGHAN.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2014;58(2):258-74.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Benninga MA, Faure C, Hyman PE, St James Roberts I, Schechter NL, Nurko S.

Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Neonate/Toddler.

Gastroenterology.

2016.

PubMed abstract

Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M.

Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents.

Gastroenterology.

2016.

PubMed abstract

Roles of the Medical Home

Clinical Assessment

Overview

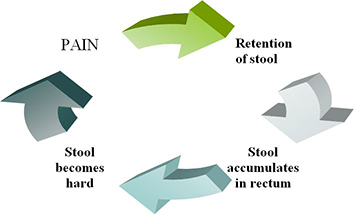

- Poor involuntary or voluntary neurologic control and muscle coordination in the GI tract, which can be due to chronic overstretching from retained or backed-up stool, surgical disruption, abnormal anatomy, and decreased neuroregulation and sensation

- Dietary factors including inadequate fluid (especially water); inadequate fiber (found in whole grains, fruits, and vegetables); constipating foods (such as infant rice cereal, bananas, and cheese); lack of stimulating foods (e.g., prunes, apples, pear juice); and unstructured grazing (instead of eating regular meals, thus losing the peristaltic stimulus of a food bolus)

- Emotional factors including anxiety over painful stools, withholding behaviors that develop after having painful/hard stools, toileting accidents or stressful training, anxiety about asking to use the bathroom, and difficulty relaxing while in the bathroom

- Lifestyle factors including inadequate exercise and lack of access to unhurried toilet time after meals or when the rectum feels full

- Intake of certain medications (antacids with calcium or aluminum, antidepressants, antihistamines, narcotics, some antihypertensives, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics) or iron supplements (however, the iron fortification in infant formula is not considered a contributing factor). See Medications That Can Affect Colonic Function (IFFGD) for a more complete list.

Pearls & Alerts for Assessment

Red flags for organic diseaseConsider further causes of constipation if there is delayed passage of meconium; onset <1 month of age; vomiting with abdominal pain or distension, or bilious vomiting; blood mixed into the stool; pain-causing night awakenings; weight loss; or abnormal neurologic findings (e.g., abnormal anal tone, absence of anal wink, sacral tuft of hair) or abnormal gastrointestinal tract findings (e.g., peri-anal fistula or tags, imperforate or anteriorly placed anus).

When to referReferral to a subspecialist is recommended only when there is concern for organic disease or when constipation persists despite appropriate therapy.

Causes of fecal incontinenceWhile fecal incontinence (including soiling and encopresis) usually is due to constipation, 20% of incontinent children actually have non-retentive fecal incontinence (defined as socially inappropriate loss of control of the bowels not caused by constipation or another medical condition). [Koppen: 2016]

Screening

Presentations

- Straining in toddlers and older children, although in infants, straining and crying to pass normal, soft stool (known as dyschezia) is common and should improve once the infant has more muscle coordination

- In toddlers and children, behaviors that reflect attempts to not pass stool, such as standing and/or crossing their legs while straining or hiding when they need to pass stool

- Infrequent stools for the child’s age and/or very irregular patterns of stooling

- Tearing/bleeding from the rectum (anal fissures, hematochezia)

- Fecal soiling due to leakage around large, obstructing stool and decreased sensitivity and awareness of the presence of stool at the anus. Soiling (stool staining in the underwear) and encopresis (loss of full-size stool) are often used interchangeably and are both included in the term “fecal incontinence” used in current literature and guidelines.

- Pebbly or bulky hard stools (can clog the toilet). See Bristol Stool Scale (below), types 1-2.

- Withholding and/or accidents due to anxiety about painful stools

- Onset of abdominal pain with meals, due to stimulation of the gastro-colic reflex resulting in cramping as peristalsis meets firm stool that is hard to move

- Less commonly, vomiting or reflux

Diagnostic Criteria

- Two or fewer defecations per week

- History of excessive stool retention

- History of painful or hard bowel movements

- History of large-diameter stools

- Presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum

- At least 1 episode/week of incontinence after the acquisition of toileting skills

- History of large-diameter stools that may obstruct the toilet

- Two or fewer defecations in the toilet per week in a child whose developmental age is at least 4 years

- At least 1 episode of fecal incontinence* per week

- History of retentive posturing (standing or sitting with legs crossed or straight and stiff to avoid passing stool, or hiding and becoming red in the face while straining to hold in stool) or excessive volitional stool retention

- History of painful or hard bowel movements

- Presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum

- History of large diameter stools that can obstruct the toilet

*Of note, while constipation causes the majority of childhood fecal incontinence (including soiling and encopresis), 20% of incontinent children actually have non-retentive fecal incontinence (defined as socially inappropriate loss of control of the bowels not caused by constipation or another medical condition). [Koppen: 2016]

Differential Diagnosis

- Normal stooling

- Infant dyschezia

- Normal early childhood developmental phase (typical for kids ages 16-24 months) – usually situational (fear of toilet training or school bathroom avoidance) Non-retentive fecal incontinence (defined as socially inappropriate loss of control of the bowels not caused by constipation or another medical condition). [Koppen: 2016]

- Attention-deficit, autism spectrum disorder, or cognitive delays

- Sexual abuse [Philips: 2015]

- Colonic inertia or genetic predisposition

- Low fiber or fluid diet

- Inadequate nutrition

Medical Conditions Causing Constipation

- Hirschsprung disease

- Spina bifida

- Cerebral palsy

- Autism

- Hypothyroidism or electrolyte disturbances

- Systemic disorders, including diabetes mellitus, celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, autoimmune conditions, panhypopituitarism

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B

- Developmental delays

- Tube feeding

- Anxiety (fear of using public restrooms, asking permission to go to the bathroom at school, etc.)

- Inadequate intake of fluid and nutrition or excessive vomiting (not enough in, not enough out)

- Drug, supplement, or toxin effect (e.g., analgesics, anticholinergics, antacids, psychotropics, iron, lead, botulinum)

- Obstruction or pseudoobstruction

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Specific dietary protein allergy (e.g., cow milk protein)

- Anatomical malformations or masses of the intestinal tract

- Spinal cord dysfunction, tethered cord, tumors of the spinal cord

- Sensory integration disorder

[Tabbers: 2014] [Philips: 2015]

History & Examination

Current & Past Medical History

- Was there passage of meconium after 48 hours of birth?

- Is there difficulty or delay in stooling that has been present at least 2 weeks?

- What is the consistency and appearance of the stool? Communication about different stool consistencies can be made simpler

using stool scales or by looking at samples or pictures that families bring to discuss. Check if there are hard, pebble-like,

or fragmented stools.

- Stool scales used for children include the

Bristol Stool Form Scale (

383 KB) (free)

and Amsterdam Infant Stool Scale

(available for a cost). [International: 2016]

[Tabbers: 2014]

383 KB) (free)

and Amsterdam Infant Stool Scale

(available for a cost). [International: 2016]

[Tabbers: 2014]

- Apps to track stool type, frequency, and related information (e.g., Poo Keeper)

- Stool scales used for children include the

Bristol Stool Form Scale (

- Are any of the following present?

- Infrequent stooling that is associated with pain

- Is the pain associated with a sense of urgency to stool, and is the pain relieved with the passage of stool?

- Sharp, cramping abdominal pain

- Typical location is near the belly button or lower left or right side.

- Typical timing is intermittent daytime pain, during or shortly after a meal (typically dinner), or with exercise.

- Stool withholding or fear of passing stool

- Stool leaking/fecal soiling (involuntary staining of the underpants, also known as encopresis) or stool accidents not appropriate for developmental age. [Hyams: 2016] Soiling is more commonly associated with constipation, whereas loss of full-size stool may be associated with functional non-retentive fecal incontinence (FNRFI). [Koppen: 2016] Fecal incontinence that occurs without evidence of stool retention or slowed colonic transit time, or is in conjunction with urinary incontinence, or is associated with stress or trauma in the child’s life, should trigger the clinician to consider a diagnosis of functional non-retentive fecal incontinence.

- Toilet clogging (large, bulky stools)

- Dyschezia

- Sense of incomplete bowel movements/unable to fully empty

- Early satiety/fills up fast, sense of bloating or nausea, prefers to snack rather than have a full meal

- Change in eating patterns (volume/pace) associated with changes in bowel frequency

- Irritability when no stool has passed recently

- School absence related to constipation or abdominal pain

- What is the toileting schedule or pattern? The Stool Diary Using Bristol Stool Form Scale (NIH) (

147 KB) can help families record this information.

147 KB) can help families record this information.

- What is the timing and composition of meals, snacks, and fluid intake? A 3-day intake diary may be useful to review.

- Is there excessive milk or juice intake?

- Is there a pattern of eating small amounts throughout the day (grazing pattern of eating)?

- Ask about frequency of exercise. For children with limited mobility, ask about time in standers or walkers.

- Identify chronic illnesses and medical conditions, including prior procedures and surgeries. Obtain information about any prior GI studies or tests and any medical providers already consulted for this issue.

- Identify all over-the-counter and prescription medications, fiber, and natural remedies used.

Physical Exam

Constipation is present if the history suggests constipation, and there is a palpable fecal mass on abdominal exam and/or a large amount of stool present on rectal exam. It is helpful to know that a stool ball may be present in 85% of children in the morning, so a fecal ball on rectal exam does not automatically require medical intervention.

General

Evaluate hydration status, pain status, ability to take oral fluids and medications, and mental status.

Growth Parameters

Evaluate growth curve for weight loss, short stature, or low weight for height/length or declining BMI. Failure to thrive may be an indication of Hirschsprung disease, impaction, or neurenteric problems. [Tabbers: 2014]

Abdomen

Check for bowel sounds, distension, focal or diffuse tenderness, palpable fecal mass, or surgical scars.

Testing

Laboratory Testing

Imaging

Abdominal X-rays should be obtained if there is concern for bowel obstruction or perforation (2-views) or a foreign body (foreign body series).

In unusual cases, studies such as barium enemas, manography, endoscopy, GI biopsies, and emptying times may be useful diagnostic tools, but these are not routinely indicated and consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist would be advised.

Un-prepped barium enema can be used to identify a transition zone, such as with Hirschsprung disease, when there is a gush of fluid or stool following a digital rectal exam or history of failing to pass meconium in a timely fashion. This is most useful diagnostically in children <2 years of age. The barium used can also help pass stool, therapeutically.

MRI of lumbosacral spine to evaluate for tethered cord (e.g., for history of motor neuron issues, findings of sacral lipoma or tuft). Spinal ultrasound may be performed as screening for newborns with abnormal sacral findings.

Not generally ordered by primary care clinicians, the following studies may be ordered by a pediatric gastroenterologist as further evaluation, if indicated:

- Anorectal manometry can help identify increased rectal sensory threshold (i.e., difficulty sensing stool burden), paradoxical contraction of pelvic floor muscles and external anal sphincter, or failure of relaxation of the internal anal sphincter. This requires a cooperative child.

- Colonic manometry can assess sensation and tone and may be used in the assessment of sensorimotor function.

- Anal sphincter electromyography can be used to evaluate the activity of the external anal sphincter and puborectalis muscles. This can be used in biofeedback to support more efficient, effective passage of stool.

- Colonic transit time (CTT) may assist in differentiating between fecal incontinence that is related to constipation (in which the transit time may be slower than normal) and functional non-retentive fecal incontinence, which is associated with normal CTT. CTT can be assessed via abdominal X-ray after swallowing a radio-opaque marker or by colonic transit scintigraphy. [Koppen: 2016]

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pediatric Gastroenterology (see NW providers [0])

Colorectal Care Clinics (see NW providers [0])

Pediatric Neurosurgery (see NW providers [1])

Treatment & Management

Pearls & Alerts for Treatment & Management

Most recommended medication for maintenance therapyThe most highly recommended medication for maintenance therapy for pediatric functional constipation is polyethylene glycol (PEG). Lactulose, milk of magnesia, mineral oil, and stimulant laxatives can be added or used as second-line therapies. [Tabbers: 2014] While current guidelines support use of lactulose over the other second-line therapies, a 2016 Cochrane review found it inferior to mineral oil (liquid paraffin) or milk of magnesia. [Gordon: 2016]

Maintenance therapyPolyethylene glycol (PEG) and lactulose are considered the safest medications for daily maintenance therapy in children. [Tabbers: 2014] Maintenance therapy is generally recommended to be continued for at least 6 months and then gradually discontinued with monitoring of stools to make sure the tapering is tolerated. [Tabbers: 2014] Some experts advised maintenance therapy for up to 18 months. Early discontinuation of maintenance therapy by families or clinicians is a common reason for constipation to recur. Dosing guidance is in Pharmacy & Medications, below.

Clean-outs before maintenance therapyChildren with moderate to severe constipation typically need a “clean-out” prior to initiating maintenance therapy. The goal of a clean-out is to stimulate and soften bowel movements, not to obtain clear liquid stools needed to prep for a colonoscopy.

Thickeners and PEGStarch- and xanthan gum-based thickeners are used to increase the density of fluids to reduce the risk of aspiration for children with swallowing dysfunction. Recent research suggests that interactions between starch-based thickeners and PEG may result in inconsistent thickening and thus reduce their effectiveness. To date, xanthan gum-based thickeners do not seem to be affected by PEG. [Carlisle: 2016]

Aspiration RiskWhile constipation is generally treated the same way in children with neurological impairment (NI) as for children without neurological impairment, severe pneumonias have been linked to aspiration of polyethylene glycol and other oral laxatives in children with NI. [Romano: 2017]

Offsetting costs of diapers for older childrenDiapers are a large health care expense. Generally, Medicaid will cover the cost of diapers for the incontinent child after age 3 through a home care company with a clinician’s prescription and letter of medical necessity. Less frequently, private payers can be convinced to do this.

How should common problems be managed differently in children with Constipation?

Over the Counter Medications

Common Complaints

Systems

Gastro-Intestinal & Bowel Function

62 KB), scheduled enemas, or surgical interventions. The following information

explains developmental approaches to treatment of constipation, prevention,

and complications. Medications (including fiber supplements) and

complementary & alternative approaches are addressed in subsequent

sections.

62 KB), scheduled enemas, or surgical interventions. The following information

explains developmental approaches to treatment of constipation, prevention,

and complications. Medications (including fiber supplements) and

complementary & alternative approaches are addressed in subsequent

sections.Educational resources for parents may include:

- Management and Prevention of Constipation in Children (Medical Home Portal)

-

Let’s Talk About Constipation and Home Bowel Program (Intermountain Healthcare) (

)

)

- Constipation in Children: Understanding and Treating This Common Problem (Video)

Infancy

A common time for infants to become constipated is during the introduction of solid foods and cereals to the diet. Infants may express more irritability or arch their back and cry when passing hard stool. Clinicians should provide education about normal stooling patterns in infants and manage constipation when it arises. There is insufficient evidence to routinely recommend use of a probiotic or hydrolyzed formula as first-line treatments of constipation in infants; however, in infants who do not respond to laxative therapy, a 2- to 4-week trial of a hypoallergenic formula (without cow’s milk protein) may be considered. For breastfed infants, a maternal avoidance diet of cow’s milk protein could alternatively be considered. It is advised for families to avoid or limit rectal manipulations to encourage regular bowel movements in infants; this can be associated with more problems like fissures, pain, and worsening symptoms.

Toilet Training

Constipation occurs more frequently in children who are toilet training. Painful stooling can lead to irritability or anxiety in children and increased reluctance to use the toilet. Clinicians should explain to parents that the development of continence of urine and of stool often does not happen simultaneously, and fecal incontinence occurs from involuntary overflow of stool and not from voluntary defiance. Clinicians can instruct parents to:

- Ensure easy access to the potty or toilet, which should be comfortable getting on, off, and while sitting.

- Provide supportive seating. The child should be able to rest his or her feet on a stool or the floor. Handles can provide additional support.

- Provide adequate time to pass stool. Many children will have better success with passing stool if they regularly take advantage of the gastro-colic reflex after meals.

- Gently encourage efforts to use the potty. Avoid reprimanding or shaming children when they have accidents. Use of small rewards like stickers can be helpful. Keeping a stool diary can be motivating as well as informative.

Older children and adolescents may develop constipation when they attend school or are away from home. Many children feel anxious or embarrassed about using unfamiliar bathrooms to pass stool. In school, limited time and access to the bathroom make it harder to relax and pass stool. Inattentive or oppositional behaviors also can contribute to constipation. This can result in the painful and retentive cycle of constipation described above. This is often detected when the internal anal sphincter loses sensitivity, and encopresis occurs. Parents can help children in this situation by discussing and planning ahead for bowel movements outside the home and normalizing bodily functions to reduce any shame the child feels about stooling.

Setting a schedule to sit on the toilet for 5-10 minutes after meals, and possibly after school, may help children form good bowel habits. This time should be relaxed and not rushed. The child should be able to sit comfortably on the toilet with feet on a stool to facilitate good positioning with knees up. Blowing into a straw to inflate a balloon on the end or holding the knees or pillow are good ways to encourage proper Valsalva breathing techniques during active pushing. Boys may benefit from sitting to pee, providing an opportunity to pass stool at the same time. Keeping a bowel diary and using incentives to reward compliance with the stool schedule may be motivating to older children as well as for younger kids who are potty training. These techniques help children with constipation and also can be used for treatment of functional non-retentive fecal incontinence. [Koppen: 2016]

Prevention of Constipation

Although there is little supporting evidence, commonly given advice is to ensure healthy eating habits and diet, regular exercise, adequate fluid and fiber intake, and relaxed toileting, particularly after larger meals. Ensure that children and youth with neurologic impairment or tube feeding obtain adequate fiber and water intake. [Romano: 2017]

Fiber: A healthy diet helps ensure adequate nutrition and fiber intake and may help prevent constipation. A healthy diet includes at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables daily in addition to peas, nuts, beans, and fiber-rich cereals and breads. Examples of particularly high-fiber foods include apples, pears, prunes, apricots, plums, raisins, raw tomatoes, peas, beans, broccoli, and sweet potatoes. Low-fiber or constipating foods include rice, cooked carrots, dairy products, bananas, and cereals or breads that are not high in fiber. [Healthy: 2017] MyPlate (USDA) offers personalized eating plans for families and interactive tools to help plan and assess food choices. Refer families to How to Get Your Child to Eat More Fruits & Veggies (AAP) for practical suggestions.

Traditionally, recommended daily grams of dietary fiber can be estimated using the child’s age plus 5-10; however, newer U.S. dietary guidelines advise higher fiber intake of 14g of fiber for every 1,000 calories in the diet. The following summarizes fiber intake goals for children and young adults based on the recommended high fiber goal: [U.S.: 2020]

- Males

- Age 2-3 years – 14 g

- Age 4-8 years – 20 g

- Age 9-13 years – 25 g

- Age 14-18 years – 31 g

- Age 19-30 years – 34 g

- Females

- Age 2-3 years – 14 g

- Age 4-8 years – 17 g

- Age 9-13 years – 22 g

- Age 14-18 years – 25 g

- Age 19-30 years – 28 g

For children >1 year old who are formula dependent, prescribe a formula with fiber unless it is not available or tolerated. More information about over-the-counter fiber supplements can be found below, toward the end of the Pharmacy & Medications section.

Scheduled Meals: Grazing, particularly on low-fiber foods, may increase the risk of constipation because it 1) decreases the size of regular meals and the resulting bolus of food that should propel stool through the gut and 2) reduces the gastro-colic reflex.

Water Intake: In the US, there are no commonly accepted recommendations for daily water intake for children. [Healthy: 2016] An Australian resource recommends 1.2-1.5 liters (around 5-6 cups) daily of water for children ages 4-13. [HealthyKids: 2015] Some clinicians use the Holliday-Segar method to estimate daily fluid requirements for a child: [Meyers: 2009] Fluid intake prescriptions for tube-fed children should include both the needed total liquid nutrition volume, total calories needed per day, plus additional free water to meet daily fluid requirements.

Holliday-Segar method for calculating daily fluid requirements:

- 100 ml/kg for the 1st 10 kg of weight

- 50 ml/kg for the 2nd 10 kg of weight

- 20 ml/kg for the remaining weight

- 100 ml/kg/24-hours - 4 ml/kg/hr for the 1st 10 kg

- 50 ml/kg/24-hours - 2 ml/kg/hr for the 2nd 10 kg

- 20 ml/kg/24-hours - 1 ml/kg/hr for the remainder

Exercise: Recommend that children exercise daily for at least an hour. While there is a lack of high-quality evidence about using exercise as treatment for constipation, children who exercise regularly are at decreased risk for constipation. [Koppen: 2015] For children with restricted mobility, encourage time spent in upright positioning, such as in a stander or walker; there is very limited evidence that this positioning, which uses gravity, may help decrease pain associated with passing stools in children with cerebral palsy. [Rivi: 2014]

Relaxation: Discuss the benefits of relaxation. Ensure that children have regular, unrushed time on the toilet, ideally at least 5 minutes after meals. [Koppen: 2015] Increasing fluid intake leads to increased urination, which can help with anal relaxation. Sitting in a warm tub may be helpful, too. Deep breathing and conscious relaxation of the muscles involved in stool elimination can also help a child to relax; however, there is not sufficient evidence to recommend using biofeedback or behavioral therapies for routine treatment of children with functional constipation. [Tabbers: 2014]

Further information for clinicians:

- Toilet Training Children with Complex Medical Conditions - Information to help determine when a child with special health care needs may be ready to train.

-

Non-Pharmacological Treatment of Functional Constipation in Children (

62 KB) - Treatment details related to education, toilet training,

behavioral therapy, biofeedback training, fiber, fluid, and

exercise; an excerpt from [Koppen: 2015].

62 KB) - Treatment details related to education, toilet training,

behavioral therapy, biofeedback training, fiber, fluid, and

exercise; an excerpt from [Koppen: 2015].

Constipation, particularly chronic, can lead to pain, rectal fissures, rectal prolapse, hemorrhoids, encopresis, enuresis, urinary tract infections, ureteral obstruction, rectal ulcer (solitary), bacterial overgrowth, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy, and psychosocial disturbances.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

General Counseling Services (see NW providers [1])

Pharmacy & Medications

Based on current guidelines, the most highly recommended medications for maintenance therapy for functional constipation are polyethylene glycol and lactulose, in that order. Milk of magnesia, mineral oil, and stimulant laxatives can be added or used as second-line therapies. [Tabbers: 2014] However, the data supporting use of laxatives other than PEG are not as clear; a 2016 Cochrane review cited limited evidence for use of mineral oil or lactulose as second-line treatments to PEG. Maintenance therapy should be continued for several months and then gradually discontinued as tolerated. [Tabbers: 2014] Many experts advise consistent use of medications to achieve 1-2 mushy stools daily for at least 6, and sometimes up to 18 months, to permit the cycle of fear and pain from defecation to fully resolve. There is not sufficient evidence to support the widespread myth that laxatives cause physical dependency; although, constipation may recur in some people once the laxative is discontinued. In this situation, parents may need reassurance that treatment of chronic constipation is important to the child’s long-term health, particularly if there is a history of encopresis or slow motility.

A bowel clean-out may be indicated at the onset of treatment and periodically if a child tends to become intermittently “backed up.” Because the goal of a bowel clean-out for treatment of constipation is to stimulate motility and soften stool already within the digestive tract, stools do not need to reach a clear liquid consistency (in contrast to bowel clean-outs prior to colonoscopy).

Oral Iso-Osmotic Laxatives

Osmotic laxatives cause the intestinal tract to hold more fluid. Side effects may include gas, bloating, diarrhea, nausea, cramping, and thirst.

Polyethylene Glycol 3350 (e.g., PEG 3350, MiraLAX, GlycoLax) This is considered first-line treatment for pediatric constipation. It is iso-osmotic in maintenance doses, so it does not cause electrolyte abnormalities, but in clean-out doses is osmotic. Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 3350 over-the-counter oral laxative (MiraLAX) has been added to the Potential Signals of Serious Risks List (FDA) for possible neuropsychiatric adverse effects; however, the FDA decided that no action is necessary at this time based on available information.

- For clean-out of fecal impaction phase: 1-1.5 g/kg/day x 3-6 days, maximum 100 g/day

- For maintenance phase: 0.2-0.8 g/kg/day (can be divided in 1-3 doses), maximum 17 g/day, often continued for several months

- H2O ratio: 1 teaspoon to 2.5 oz. liquid; 17 g to

4-8 oz. liquid or 5 g = 1 teaspoon

- 17 g = 1 capful = 1 heaping tablespoon

- Do not count the PEG fluid volume in the child’s total daily maintenance fluid volume.

- Avoid mixing with fat-containing liquids (like milk or formula) or in foods.

- Works best if consumed within 20 minutes.

- Liquid (10 g/15 mL sol) or packets: 1-2 g/kg 1-2 times daily, max 40 g, in divided doses [Tabbers: 2014]; or 1-3 mL/kg/day of the 70% solution.

- Phillips Milk of Magnesia original strength 400

mg/5 mL suspension [Tabbers: 2014]

- 2-5 years: 0.4-0.12 g/day or 5-15 mL/day in 1-2 divided doses

- 6-11 years: 1.2-2.4 g/day or 15-30 mL/day in 1-2 divided doses

- ≥12 years: 2.4-4.8 g/day or 30-60 mL/day in 1-2 divided doses

- PediaLax chewables

- 2-5 years: 1-3 tablets

- 6-11 years: 3-6 tablets

- Dulcolax soft chews 1200 mg saline laxative

(containing 500 mg magnesium). Take with 8 oz of liquid.

- 6-12 years: 1-2 chews/day (can be taken once or divided)

- ≥12 years: 2-4 chews/day (can be taken once or divided)

Magnesium citrate (e.g., Citroma, GoodSense) - a saline laxative. Can cause hypermagnesemia and hypophosphatemia; check labs every 3-6 months.

- Citroma or GoodSense (1.75 g/30 mL) solution

- 2-6 years: 3.5-5.25 mg (60-90 mL) daily

- 6-12 years: 5.25-12.25 mg (90-210 mL) daily

- >12 years: 12.25- 17.5 mg (195-300 mL) in single or divided doses

- Citroma or GoodSense 100 mg tablets

- >12 years: 200-400 mg (2-4 tablets) in single or divided doses

Magnesium also comes in a variety of other formulations, doses, and flavors.

Sorbitol (70% oral solution) - a sugar alcohol derived from fruit. Can cause hypermagnesemia and hypophosphatemia, flatulence, abdominal pain, and cramping.

- 2-11 years: 2 mL/kg used once

- >=12 years: 0-150 mL used once

Lubricant Laxatives

This type of laxative surrounds the outside of the stool with a slippery coating to enable smoother passage of stool and to keep water in the stool.

Mineral oil (e.g., Kondremol) [Tabbers: 2014] - This is considered second-line therapy for constipation. Avoid use in ages less than 2 due to risk of oil aspiration. Can mix in pudding or yogurt to decrease risk of aspiration.

- 2-11 years: 30-60 mL daily

- ≥12 years: 60-150 mL of plain mineral oil daily given as a single dose

Oral Stool Softeners

This type of laxative helps mix moisture into the stool to make it softer and reduce straining. Stool softeners do not trigger more frequent stool passage.

Sodium docusate (e.g., Colace, PediaLax Liquid Stool Softener). Requires a full-fat diet.

- In liquid (50 mg/15 mL), syrup (60 mg/15 mL), or

capsules (50, 100, 240, and 250 mg)

- 2-11 years: 50-150 mg/day (single or divided)

- ≥12 years: 50-360 mg/day (single or divided)

- PediaLax [Tabbers: 2014]

- 2-11 years: 1-3 tablespoons mixed with milk or juice

The harshest type of laxatives, stimulant laxatives are considered second-line therapy for constipation. Causes increased contractions of the gut to help move stool out within several hours. These are most often used to facilitate a clean-out. Use should be limited to a few days at most. Stimulated bowels feel crampy; encourage children to sit on the toilet when these cramps occur.

Senna/sennosides (e.g., ExLax, Little Tummies, Senokot) - in tablets (8.6 mg, 15 mg, and 25 mg doses), chewables (15 mg tablets), liquid and syrup (8.8 mg/5 mL) [Tabbers: 2014]

- 2-5 years: 2.5-5 mg/1-2 times daily

- 6-12 years: 7.5-10 mg/day

- >12 years: 15-20 mg/day

- 2-5 years: 167-333 mg (5-10 mL) daily

- 6-15 years: 333-500 mg (10-15 mL) daily or divided

- 2-6 years: 166.5-666 mg/day

- 6-12 years: 333-999 mg/day

- 3-10 years: 5 mg/day

- >10 years: 5-10 mg/day

These help evacuate the rectum by coating the stool and making it slippery. Stool typically is evacuated within an hour. Suppositories are not routinely advised for daily use.

Glycerin (e.g., Pedia-Lax, Fleets) - solid suppository in 1, 1.2, 2, and 2.8 mg sizes or liquid suppository (i.e., liquid delivered via rectal applicator)

- Solid suppository

- <4 months: 0.5 mg (1/2 pediatric suppository)

- 4 months--5 years: 1 mg (1 pediatric suppository)

- 6 years-adolescence: 2 mg (1 adult suppository)

- Pedia-Lax liquid glycerin suppository (2.8 mg/2.25

mL bottle)

- 2-5 years: 1 suppository given rectally x 1 via rectal applicator

- 1-2 years: 1/2 suppository

- 2-11 years: 1/2-1 suppository

- ≥12 years: 1 suppository

Enemas flush out the rectum and act more quickly than oral laxatives. Side effects can include incomplete evacuation of the fluid, which can lead to discomfort, distension, or electrolyte imbalances. There are other do-it-yourself and commercial enemas, but due to the risks, only 2 selected osmotic enemas are presented here.

Saline enema (e.g., Pedia-Lax, Fleet Saline) - The FDA announced in 2014 that using these more than once daily can result in serious harm to the kidneys and should NEVER be given to children under 2 years of age. [Tabbers: 2014] [U.S.: 2016]

- Pedia-Lax (monobasic sodium phosphate 9.5 g and

dibasic sodium phosphate 3.5 g/66 mL bottle)

- 2-4 years: 1/2 bottle

- 5-11 years: 1 bottle rectally x 1

- Adult saline enema (Fleets - 19 g monobasic sodium

phosphate monohydrate and 7 g dibasic sodium phosphate

heptahydrate/188 mL bottle)

- ≥12 years: 1 bottle

- 2-11 years: 30-60 mL daily

- ≥12 years: 60-150 mL daily

- 2-12 years: 100 mg (1 DocuSol Kids tube)

- ≥12 years: 283 mg (1 DocuSol or Enemeez Mini tube)

- Alternative dosing [Tabbers: 2014]

- <6 years: 60 mL daily

- >6 years: 120 mL daily

- 2-10 years: 5 mg (1/2 enema) daily

- >10 years: 5-10 mg (1/2-1 enema) daily

Other oral medications are occasionally used to treat adult chronic constipation, such as lubiprostone (Amitiza), linaclotide (Linzess, Constella), prucalopride (Reselor, Motegrity), tegaserod (Zelnorm), and alvimopan (Entereg). These medications SHOULD NOT be used in the primary care management of pediatric constipation.

Fiber/Oral Bulk-Forming Laxatives

Fiber supplements have not been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of pediatric constipation. Limited evidence shows that additional fiber improves constipation and may help in prevention. [Tabbers: 2014] Fiber is the non-digestible carbohydrate portion of many foods. Both soluble and insoluble fibers are important to digestive tract health.

Insoluble fiber: Helps “bulk” the stools and promotes normal contractions and motility so stools pass more quickly through the GI tract. Insoluble fiber food sources include wheat bran, whole grains (cereal, pasta, and bread), seeds, nuts, leafy greens, broccoli, and the skins of many fruits and root vegetables. Other sources are as follows:

Soluble fiber: Slows digestion by attracting water and forming a gel, which allows time in the GI tract for nutrients to be absorbed, helps regulate blood sugar, and potentially reduces LDL cholesterol. In general, soluble fiber is less helpful than insoluble fiber in fighting constipation. Soluble fiber food sources include oatmeal, lentils, seeds and beans, psyllium, chicory and inulin, and certain berries. Other sources are as follows:

Over-the-counter fiber supplements: These include but are not limited to:

- Methylcellulose (Citrucel) contains insoluble semi-synthetic fiber. It is non-fermentable, so not as likely as fermentable fiber to produce gas.

- Polycarbophil (FiberCon) contains insoluble synthetic fiber and is also non-fermentable.

- Fiber gummies can contain either or both soluble and insoluble types of fiber.

- Wheat dextrin (Benefiber) contains soluble fiber, which is fermentable in the gut.

- Psyllium (Metamucil) contains about 70% soluble fiber and 30% insoluble fiber. It is partially fermentable and may cause gas.

- Barley malt extract (Maltsupex) contains soluble fiber.

- Guar gum fiber (Reliefiber) is partially hydrolyzed soluble fiber extracted from guar beans and is less fermentable in the gut.

Specialty Collaborations & Other Services

Pharmacies / Prescriptions (see NW providers [1])

Complementary & Alternative Medicine

Acupuncture: Acupuncture is gaining some supporting evidence for use in adults with constipation, and there is emerging evidence for biofeedback use in adults with dys-synergic defecation. [Broide: 2001] [Rao: 2015] However, acupuncture is not currently recommended for routine treatment of childhood constipation due to lack of supporting evidence in this population.

Behavioral therapy: While behavioral therapy lacks evidence to treat functional constipation, behavioral supports can encourage healthy toileting practices and can be used to address non-retentive fecal incontinence.

Biofeedback: Biofeedback, used to guide pelvic floor contractions and relaxation, is gaining some supporting evidence for use in children with dyssynergic defecation. [Jarzebicka: 2016]

Dairy avoidance: A 2- to 4-week trial of avoidance of cow’s milk protein (CMP) may be indicated in the child with intractable constipation that does not respond to laxatives. [Tabbers: 2014] Since CMP intolerance or allergy is not typically IgE mediated, blood levels, patch, or skin prick test are not routinely recommended for diagnosis. [Vandenplas: 2015] For breastfed babies, a maternal elimination diet may be trialed.

Electrical stimulation: Interferential electrical stimulation has some evidence for use in treatment of functional constipation in children, in conjunction with pelvic floor muscle therapy.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): FMT is undergoing study as a possible treatment for constipation in children and adults. [Avelar: 2020] It is not an evidence-based treatment for pediatric functional constipation at this time.

Home remedies: Current clinical practice guidelines do NOT recommend use of natural remedies or alternative therapies for treatment of functional constipation in large part because they often lack safety studies and may be unhealthy or dangerous, especially in high doses. Be aware of some remedies that caregivers may be using:

- Lemon juice to stimulate contractility.

- Molasses by mouth can have stimulating effects but is not currently recommended for routine treatment of constipation, although one study demonstrated similar effectiveness to polyethylene glycol 3350. (A hospital in Utah no longer performs or recommends milk and molasses enemas due to a sentinel event.)

- Aloe is thought to help with occasional constipation, yet it can be unsafe at high doses and therefore should not be used for routine treatment of constipation. [WebMD: 2015]

Prebiotics: These are non-digestible food ingredients that help propagate healthy gut bacteria. All prebiotics are fiber, but not all fibers are prebiotic. Examples of prebiotics include inulin, wheat dextrin, and polydextrose. [Slavin: 2013]

Ask the Specialist

When do children need admission to the hospital for constipation clean-outs?

With persistence of the parents and detailed education and encouragement from the primary care provider, almost all children with constipation, including children with developmental difficulties, can do colon or bowel clean-outs at home. Reasons to send a patient to the emergency room may include suspected bowel obstruction (bilious emesis, signs of obstruction on abdominal X-ray, severe abdominal distention) or inability to tolerate any kind of oral intake.

When do primary care physicians need to refer children with constipation to the pediatric gastroenterology clinic?

Most children with constipation can be successfully managed by primary care physicians. Reasons to refer to the pediatric gastroenterology clinic include presence of alarming signs or symptoms suggestive of organic disease, relapse of symptoms after initial successful treatment, and no improvement after appropriate treatment.

Is a “stool ball” an indication for manual digital evacuation?

The only true indication for manual digital evacuation is bowel obstruction or suspected bowel obstruction due to impacted stool. Most fecal impactions can be disimpacted with oral or rectal medication, such as an enema. A stool ball may be present in 85% of children in the morning and is not an indication for manual digital evacuation.

Resources for Clinicians

On the Web

Differential Diagnosis of Constipation in Children (AAFP)

This article reviews assessment and management of constipation in children. Table 4 lists recommended diagnostic evaluation

for conditions that may be constipation in children; American Academy of Family Physicians.

Pediatric Constipation (Project ECHO Webinar)

In this 49-minute webinar video, Dr. Raza Patel, gastroenterologist at University of Utah Health, discusses constipation in

newborns, infants, and children in developing stages. He provides resources and treatment methods for providers and parents.

Presented on 1/20/2021.

PedsGI.Net

Raza Ali Patel MD, MPH, a board-certified Pediatric Gastroenterologist at the University of Utah/Primary Children’s Hospital,

developed this web-page to help patients and families and to act as a resource to others around the world with common pediatric

gastroenterology issues. The site offers quality medical information about constipation, eosinophilic esophagitis, transnasal

endoscopy, and colonoscopy.

Helpful Articles

Benninga MA, Tabbers MM, van Rijn RR.

How to use a plain abdominal radiograph in children with functional defecation disorders.

Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed.

2016;101(4):187-93.

PubMed abstract

This review describes and evaluates the value of different existing scoring methods to assess faecal loading on an abdominal

radiograph with or without the use of radio-opaque markers, to measure colonic transit time, in the diagnosis of these defecation-related

FGIDs.

Southwell BR.

Treatment of childhood constipation: a synthesis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2020;14(3):163-174.

PubMed abstract

This review covers meta-analyses and evidence for treatment of paediatric constipation since 2016 and new emerging treatments.

Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Thapar N, Benninga MA.

Functional Fecal Incontinence in Children: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Management.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2021.

PubMed abstract

Functional fecal incontinence (FI) comprises constipation-associated fecal incontinence and nonretentive fecal incontinence.

Although conventional interventions such as toilet training and laxatives successfully treat most children with constipation

associated FI, children with nonretentive fecal incontinence need more psychologically based therapeutic options. Intrasphincteric

injection of botulinum toxin, transanal irrigation and, in select cases, surgical interventions have been used in more resistant

children with constipation associated FI.; European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology.

Romano C, van Wynckel M, Hulst J, Broekaert I, Bronsky J, Dall'Oglio L, Mis NF, Hojsak I, Orel R, Papadopoulou A, Schaeppi

M, Thapar N, Wilschanski M, Sullivan P, Gottrand F.

European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of

Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children With Neurological Impairment.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2017;65(2):242-264.

PubMed abstract

With this report, European Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition aims to develop uniform guidelines for the

management of the gastroenterological and nutritional problems in children with neurological impairment.

Clinical Tools

Assessment Tools/Scales

Bristol Stool Form Scale ( 383 KB)

383 KB)

Images of 7 stool types, created to facilitate better communication among families and clinicians about bowel movements; developed

by the Bristol Royal Infirmary.

Chronic Constipation Evaluation Tool ( 84 KB)

84 KB)

Provides a format for evaluation of chronic constipation in children. Can be used as a note in a paper chart, or reformatted

for electronic medical records.

Questionnaires/Diaries/Data Tools

Stool Diary Using Bristol Stool Form Scale (NIH) ( 147 KB)

147 KB)

Printable record of stool habits for 1 week; originally from Lewis SJ, Heaton KW, Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology

- reproduced by the National Institutes of Health.

Food Record (University of Rochester) ( 151 KB)

151 KB)

A 3-day food record with instructions for parents.

Poo Keeper

Free app for smartphones or tablets, available on Apple and Google Play, is used to record stool type and consistency and

keep a bowel habits log that can be shared with a physician. Offers in-app purchases.

Patient Education & Instructions

Complete Constipation Care Package (GIKids) ( 178 KB)

178 KB)

14-page packet of printable patient education materials from the American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology

and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). Includes Constipation (pgs 1-2), Constipation and Fecal Soiling with cleanout and maintenance therapy

(pgs 3-5), Nutrition for Constipation in the First 12 Months (pg 6), Fluid and Fiber (pgs 7-9), Water Tracker (pg 10), Toilet

Training Tips (pgs 11-13), and Bowel Management Tool (pg 14).

Complete Constipation Care Package - Spanish Version ( 2.0 MB)

2.0 MB)

Complete Constipation Care Package - French Version ( 2.0 MB)

2.0 MB)

Constipation in Children: Understanding and Treating This Common Problem (Video)

An 8-minute video that helps parents and other caregivers understand constipation and what can be done to remedy it. Explains

bowel clean-outs, maintenance therapy, and the brain-gut connection; made by experts from the Pediatric Gastroenterology Clinic

at Primary Children’s Hospital.

The Poo in You - Constipation and Encopresis Video (Children's Hospital Colorado)

Excellent 5-minute video about why soiling accidents occur and what can be done to make them stop happening. Includes simple

information about the digestive process, role of colon, and medicines that may help with constipation and resulting encopresis.

The Poo In You - Deutsch /German version

Let’s Talk About Constipation and Home Bowel Program (Intermountain Healthcare) ( )

)

4-page printable handout explaining childhood constipation and home care, with scannable link to video.

Let's Talk About... Rectal Suppository (Spanish & English)

Two-page handout for caregivers about rectal suppositories for children; Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital.

Hablemos Acercos De...Supositorio Rectal ( )

)

Let's Talk About... Enemas, Small Volume (Spanish & English)

Handout for caregivers on how to give small volume enemas to children; Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital.

Hablemos Acercos De...Enema, Volumen Pequeño ( )

)

Let's Talk About... Enemas, Large-Volume (Spanish & English) ( )

)

Handout for caregivers on how to give large-volume enemas of saline, glycerin, castile soap, or phosphate solution to children;

Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital.

Resources for Patients & Families

Information on the Web

GIKids (NASPGHAN)

GIKids provides children and families with resources and easy-to-understand information on the diagnosis and management of

pediatric digestive disorders including: Celiac disease, Constipation, Eosinophilic esophagitis, GERD & Reflux, Inflammatory

Bowel Disease, plus nutrition, tests, and procedures; North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and

Nutrition (NASPGHAN).

Constipation in Children (AAP)

Learn how to know if your child is constipated and, if so, what to do about it; on HealthyChildren.org, sponsored by the American

Academy of Pediatrics.

About Kids GI Health (IFFGD)

Reliable digestive health knowledge, support, and assistance about functional gastrointestinal and motility disorders in children

and adults; International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders.

Baby's First Days: Bowel Movements & Urination (AAP)

Important points about first bowel movements on HealthyChildren.org; American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dietary Fiber (IFFGD)

Information about different kinds of fiber, how to incorporate fiber into the diet gradually, and serving sizes to help prevent

constipation; International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders.

Q & A Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI) and Pediatric Populations

Videos of experts discussed DGBI in children. The Rome Foundation is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated

to supporting the creation of scientific data and educational information to assist in diagnosing and treating DGBIs, formerly

called Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs).

Studies/Registries

Pediatric Constipation (clinicaltrials.gov)

Studies looking at better understanding, diagnosing, and treating this condition; from the National Library of Medicine.

Services for Patients & Families Nationwide (NW)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | NW | Partner states (4) (show) | | NM | NV | RI | UT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Care Clinics | 1 | ||||||||

| General Counseling Services | 1 | 10 | 213 | 30 | 298 | ||||

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 2 | 5 | 18 | 2 | |||||

| Pediatric Neurosurgery | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Pharmacies / Prescriptions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21 | ||||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAP |

| Reviewer: | Raza Patel, MD |

| 2017: first version: Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPSA; Ramakrishna Mutyala, MDR; Mark Deneau, MDR; Chuck Norlin, MDR |

Bibliography

Avelar Rodriguez D, Popov J, Ratcliffe EM, Toro Monjaraz EM.

Functional Constipation and the Gut Microbiome in Children: Preclinical and Clinical Evidence.

Front Pediatr.

2020;8:595531.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

In this review, we provide an overview of preclinical and clinical studies that focus on the potential mechanisms through

which the gut microbiome might contribute to the clinical presentation of functional constipation in pediatrics.

Benninga MA, Faure C, Hyman PE, St James Roberts I, Schechter NL, Nurko S.

Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Neonate/Toddler.

Gastroenterology.

2016.

PubMed abstract

Benninga MA, Tabbers MM, van Rijn RR.

How to use a plain abdominal radiograph in children with functional defecation disorders.

Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed.

2016;101(4):187-93.

PubMed abstract

This review describes and evaluates the value of different existing scoring methods to assess faecal loading on an abdominal

radiograph with or without the use of radio-opaque markers, to measure colonic transit time, in the diagnosis of these defecation-related

FGIDs.

Borowitz SM.

Pediatric Constipation Medication.

Medscape; (2016)

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/928185-medication. Accessed on June 2021.

Written by medical experts, information about medications used to treat constipation in children. Medications include osmotic

laxatives, lubricants, stimulant laxatives, stool softeners, and stool softeners in combination with stimulants. Sign in required.

Broide E, Pintov S, Portnoy S, Barg J, Klinowski E, Scapa E.

Effectiveness of acupuncture for treatment of childhood constipation.

Dig Dis Sci.

2001;46(6):1270-5.

PubMed abstract

Carlisle BJ, Craft G, Harmon JP, Ilkevitch A, Nicoghosian J, Sheyner I, Stewart JT.

PEG and Thickeners: A Critical Interaction Between Polyethylene Glycol Laxative and Starch-Based Thickeners.

J Am Med Dir Assoc.

2016;17(9):860-1.

PubMed abstract

Drugs.com.

Bulk-Forming Laxatives.

Drugs.com; (2008)

https://www.drugs.com/monograph/bulk-forming-laxatives.html. Accessed on June 2021.

Fiber laxatives with doses and warnings.

Gordon M, MacDonald JK, Parker CE, Akobeng AK, Thomas AG.

Osmotic and stimulant laxatives for the management of childhood constipation.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2016(8):CD009118.

PubMed abstract

Healthy Children Magazine.

Constipation.

American Academy of Pediatrics; (2017)

http://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/abdomi.... Accessed on June 2021.

How to know if your child is constipated and what to do.

Healthy Children Magazine.

Childhood Nutrition.

American Academy of Pediatrics; (2016)

http://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/nutrition/Pages/.... Accessed on 8/30/2016.

Information about what to eat and how much; healthychildren.org is from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

HealthyKids.

Choose Water as a Drink.

Department of Health - New South Wales (NSW); (2015)

http://www.healthykids.nsw.gov.au/downloads/file/kidsteens/HealthyKids.... Accessed on June 2021.

How much water children should drink.

Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M.

Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents.

Gastroenterology.

2016.

PubMed abstract

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders.

Stool Form Guide.

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders; (2016)

http://www.aboutconstipation.org/site/treatment/stool-form-guide. Accessed on 8/30/2016.

Bristol Stool Form Guide with types, images, and descriptions.

Jarzebicka D, Sieczkowska J, Dadalski M, Kierkus J, Ryzko J, Oracz G.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of biofeedback therapy for functional constipation in children.

Turk J Gastroenterol.

2016;27(5):433-438.

PubMed abstract

The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the effectiveness of biofeedback therapy as assessed by clinical improvement

as well as by changes in manometric parameters in children with constipation and pelvic floor dyssynergia (PFD).

Koppen IJ, Lammers LA, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM.

Management of Functional Constipation in Children: Therapy in Practice.

Paediatr Drugs.

2015;Oct.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Koppen IJ, von Gontard A, Chase J, Cooper CS, Rittig CS, Bauer SB, Homsy Y, Yang SS, Benninga MA.

Management of functional nonretentive fecal incontinence in children: Recommendations from the International Children's Continence

Society.

J Pediatr Urol.

2016;12(1):56-64.

PubMed abstract

Koppen IJN, Vriesman MH, Saps M, Rajindrajith S, Shi X, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM.

Prevalence of Functional Defecation Disorders in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

J Pediatr.

2018;198:121-130.e6.

PubMed abstract

This study systematically reviewed the literature regarding the epidemiology of functional constipation and functional nonretentive

fecal incontinence (FNRFI) in children. Secondary objectives were to assess the geographical, age, and sex distribution of

functional constipation and FNRFI and to evaluate associated factors.

Levy J, Volpert D.

Introduction to Constipation in Children.

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders; (2016)

https://aboutkidsgi.org/lower-gi/childhood-defecation-disorders/consti.... Accessed on June 2021.

Provides a definition, prevalence, and information about chronic constipation.

Meyers RS.

Pediatric fluid and electrolyte therapy.

J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther.

2009;14(4):204-11.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Nurko S, Zimmerman LA.

Evaluation and treatment of constipation in children and adolescents.

Am Fam Physician.

2014;90(2):82-90.

PubMed abstract

Peeters B, Benninga MA, Hennekam RC.

Childhood constipation; an overview of genetic studies and associated syndromes.

Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol.

2011;25(1):73-88.

PubMed abstract

Philips EM, Peeters B, Teeuw AH, Leenders AG, Boluyt N, Brilleslijper-Kater SN, Benninga MA.

Stressful Life Events in Children With Functional Defecation Disorders.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2015;61(4):384-92.

PubMed abstract

Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Thapar N, Benninga MA.

Functional Fecal Incontinence in Children: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Management.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2021.

PubMed abstract

Functional fecal incontinence (FI) comprises constipation-associated fecal incontinence and nonretentive fecal incontinence.

Although conventional interventions such as toilet training and laxatives successfully treat most children with constipation

associated FI, children with nonretentive fecal incontinence need more psychologically based therapeutic options. Intrasphincteric

injection of botulinum toxin, transanal irrigation and, in select cases, surgical interventions have been used in more resistant

children with constipation associated FI.; European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and

North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology.

Rao SS, Benninga MA, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, Di Lorenzo C, Whitehead WE.

ANMS-ESNM position paper and consensus guidelines on biofeedback therapy for anorectal disorders.

Neurogastroenterol Motil.

2015;27(5):594-609.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Rivi E1, Filippi M, Fornasari E, Mascia MT, Ferrari A, Costi S.

Effectiveness of standing frame on constipation in children with cerebral palsy: a single-subject study.

Occup Ther Int. .

2014.

PubMed abstract

Romano C, van Wynckel M, Hulst J, Broekaert I, Bronsky J, Dall'Oglio L, Mis NF, Hojsak I, Orel R, Papadopoulou A, Schaeppi

M, Thapar N, Wilschanski M, Sullivan P, Gottrand F.

European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of

Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children With Neurological Impairment.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2017;65(2):242-264.

PubMed abstract

With this report, European Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition aims to develop uniform guidelines for the

management of the gastroenterological and nutritional problems in children with neurological impairment.

Slavin J.

Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits.

Nutrients.

2013;5(4):1417-35.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Southwell BR.

Treatment of childhood constipation: a synthesis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2020;14(3):163-174.

PubMed abstract

This review covers meta-analyses and evidence for treatment of paediatric constipation since 2016 and new emerging treatments.

Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, Faure C, Langendam MW, Nurko S, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y, Benninga MA.

Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and

NASPGHAN.

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2014;58(2):258-74.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Thomas DW, Greer FR.

Probiotics and prebiotics in pediatrics.

Pediatrics.

2010;126(6):1217-31.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025, 9th edition.

page 146; (2020)

https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_.... Accessed on June 2021.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Possible harm from exceeding recommended dose of over-the-counter sodium phosphate products to treat constipation.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration; (2016)

http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm380757.htm. Accessed on June 2021.

Warnings, bulletins, and updates.

Vandenplas Y, Alarcon P, Alliet P, De Greef E, De Ronne N, Hoffman I, Van Winckel M, Hauser B.

Algorithms for managing infant constipation, colic, regurgitation and cow's milk allergy in formula-fed infants.

Acta Paediatr.

2015;104(5):449-57.

PubMed abstract

van Ginkel R, Reitsma JB, Büller HA, van Wijk MP, Taminiau JA, Benninga MA.

Childhood constipation: longitudinal follow-up beyond puberty.

Gastroenterology.

2003;125(2):357-63.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Varier R, Harnsberger J.

Constipation Care Plan for Primary Children's Medical Center.

Primary Children's Hospital.

04/08/2013.

WebMD.

Aloe.

WebMD; (2015)

http://www.webmd.com/vitamins-supplements/ingredientmono-607-aloe.aspx.... Accessed on June 2021.

Information and warnings about use of aloe.